Moving Beyond Protest

Moving beyond protests to stamp out racism

“You can talk about police reform, and you can talk about police accountability and I believe in all of those things,” Holston said on Zoom.

“But the reality is that every police department is really a reflection of us, who we are, and until we change who we are, the police will only continue to reflect that.”

In the week since George Floyd took his last breath under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer, hundreds of protests against police brutality and white supremacy have erupted across the United States and gone international. Some rallies, like the one in Philadelphia, saw no violence and some gatherings turned destructive and even deadly.

Throughout the unrest, United Methodists around the country have held prayer vigils, helped with cleanup, comforted the grieving and preached justice — even while trying to maintain precautions against COVID-19. Now many churches are moving into anti-racism work they expect to last long after the protests have left the headlines.

Holston is both senior pastor of Janes Memorial United Methodist Church in Philadelphia and senior adviser to the city’s district attorney. He said the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference’s Zoom call — which drew nearly 300 participants — was “a good beginning point.”

“Our young people, black and white and all colors and backgrounds, are standing up to stay, ‘Stop killing black people’ — a statement being heard round the world,” Holston told United Methodist News. But, he added, confronting racial inequality also needs to extend to all aspects of life including health care and education, as well as criminal justice reform.

For now, many United Methodists are finding ways large and small to bear witness to Christ, who came “to set the oppressed free.”

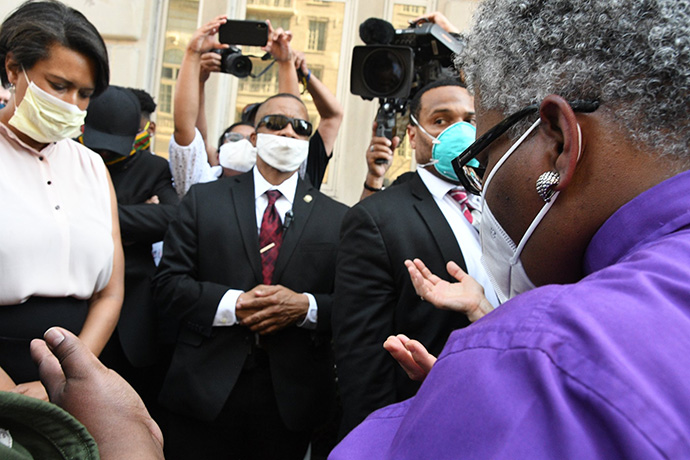

In Washington, United Methodist Bishop LaTrelle Easterling and others from the Baltimore-Washington Conference participated in a prayer vigil June 3 at the invitation of Bishop Mariann Budde, diocesan bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington.

Her area includes historic St. John’s church, where President Donald Trump visited June 1 after having Lafayette Park, across the street from both the White House and the church, cleared by means of force.

The vigil was supposed to have been held in front of St. John’s, but because the law enforcement perimeter was extended, leaders had to move a half-block down from the church.

The Rev. Will Ed Green, an associate pastor at Foundry United Methodist Church in Washington, was among the nonviolent demonstrators beside the White House on June 1 when federal law enforcement descended.

“I HELD my hands in the air alongside people who represented the true diversity of our nation as they tended the needs of their fellow protesters, providing eye wash for gas-filled eyes and water for throats parched by cries for justice,” Green wrote on Facebook.

The rate at which police in the U.S. kill black Americans is more than twice as high as the rate for white Americans, according to National Public Radio.

Minnesota previously made national news in 2016 when a St. Paul police officer shot and killed Philando Castile during a traffic stop. After Floyd died May 25 in Minneapolis police custody, protests soon roiled across the Twin Cities.

On May 26, peaceful protests gave way to violence, and the following morning, the Rev. Ronald Bell Jr. was among those who got out brooms and helped clean up.

Bell, senior pastor of predominantly black Camphor Memorial United Methodist Church in St. Paul, recounted his congregation’s tumultuous week at a June 2 United Methodist online event.

He said his focus now is helping the community deal with trauma — especially children. The church has assembled trauma kits — bags with markers and crayons and coloring books and other activities — and has invited therapists to come serve mental-health needs.

“There’s nothing more heart-wrenching than when I had to explain to my 5- and 8-year-old boys that a white police officer killed a black man,” he said. “Our community is going through grief and our role as faith leaders is to address that trauma.”

Members of the predominantly white Hamline United Methodist Church, also in St. Paul, have distributed medical supplies and food, boarded up the windows of a local women’s shelter so they couldn’t be bashed in and collected more than $7,000 for a Loving Neighbor Fund to help people in need.

“Really, the hardest thing in our neighborhood right now is that it’s become a food desert,” said the Rev. Mariah Furness Tollgaard, Hamline’s senior pastor.

“Grocery stores are closed and public transit hasn’t been running, so people can’t get to food. Restaurants are closed, and all the gas stations and convenience stores and pharmacies have either been looted, destroyed or just closed.”

In Chicago, lack of mobility has made it hard for churches to step in and help, said the Rev. Jacques Conway, district superintendent for the Chicago Southern District. The city has shut down most access to downtown.

“How do you eat this elephant?” said Conway, who spent 25 years in law enforcement, some as a chaplain. “What can you do? … People are afraid. It’s scary. The church just can’t say, ‘Stand up for unity’ and it will all be all right.”

Yet amid hardships, United Methodists have found ways to extend grace.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

In Savannah, Georgia, the mayor asked the Rev. J. Michael Culbreth and other clergy to help lead the protest and keep the peace. “Fortunately, it was a peaceful protest,” he said.

Culbreth leads ConneXion Church, multiracial United Methodist congregation formed by the merger of three churches. “We simply must work together, understand each other’s background and appreciate and respect each other as people of God,” he said.

However, he said, The United Methodist Church needs to spend more time talking about racism and race relations.

The Rev. Keith Caldwell, a United Methodist pastor and president of Nashville, Tennessee NAACP, said United Methodists have the theology to address the nation’s need. He spoke at what he called a “life-giving” rally of nearly 5,000 people May 30 in the state’s Legislative Plaza.

“We have a beautiful narrative that is in line with an ancient Hebraic understanding of liberation,” he said. “So we can bring that language to the public square, as we should, because this is what hope does.”

Belong Church, a mostly white United Methodist church start in Denver, is holding an anti-racism week June 2-7 with daily suggestions on ways the congregation can take “tangible steps” to dismantle racism, said the Rev. Genevieve Rohret-Navin.

Tuesday, June 2, was a day to write letters and make calls to lawmakers and people in power demanding change. The other days of the week will focus on supporting black businesses, black restaurants, reading books by black writers, and joining a Zoom call to discuss anti-racism work on Thursday. Sunday worship will focus on liberation and the struggle for black lives.

New City Church, a new multiracial United Methodist congregation in Minneapolis, stands in the same neighborhood where Floyd was killed. The congregation, which has been committed to anti-racism work since it started nearly three years ago, immediately responded with a prayer vigil.

Now, the congregation has set up a Solidarity Fund. The goal is to support groups doing justice work in the neighborhood, finance microloans for individuals facing economic hardship, and sustain the church’s anti-racism training.

“New City Church sees anti-racism as an expression of the Gospel because ultimately Jesus came to save us from empire,” said the Rev. Tyler Sit, the church’s pastor. “Jesus came to establish the kingdom of God, and every time we do anti-racism work, we get closer to establishing the kingdom of God.”

Holston, the Philadelphia pastor, said United Methodists have the tools to address the bigotry that blights the nation.

“Remember, racism is sin,” he said. “And as Christians, we know how to handle sin. It’s called confession and repentance. Many of us need to work on those things.”

Hahn is a UM News reporter in Nashville. Erik Alsgaard, managing editor in the Ministry of Communications for the Baltimore-Washington Conference, also contributed to this story, along with UM News team members Jim Patterson, Joey Butler and Kathy L. Gilbert.